14 October 1939: HMS Royal Oak was back in Scapa Flow after taking part in the search for the German battleship Gneisenau, the cruiser Köln and nine destroyers which were on an operation in the North Sea. This was part of a German diversionary manoeuvre to lure units of the British Home Fleet out of Scapa Flow, where they would then be attacked by the Luftwaffe. Although many ships of the Home Fleet responded, the Luftwaffe did not engage.

The search was of little use, especially to the Royal Oak which had a top speed of around 20 knots. HMS Royal Oak was unable to keep up with the rest of the fleet and had returned alone to Scapa Flow during the morning hours of 12 October. The Mighty Oak had little to offer in competition with more modern warships.

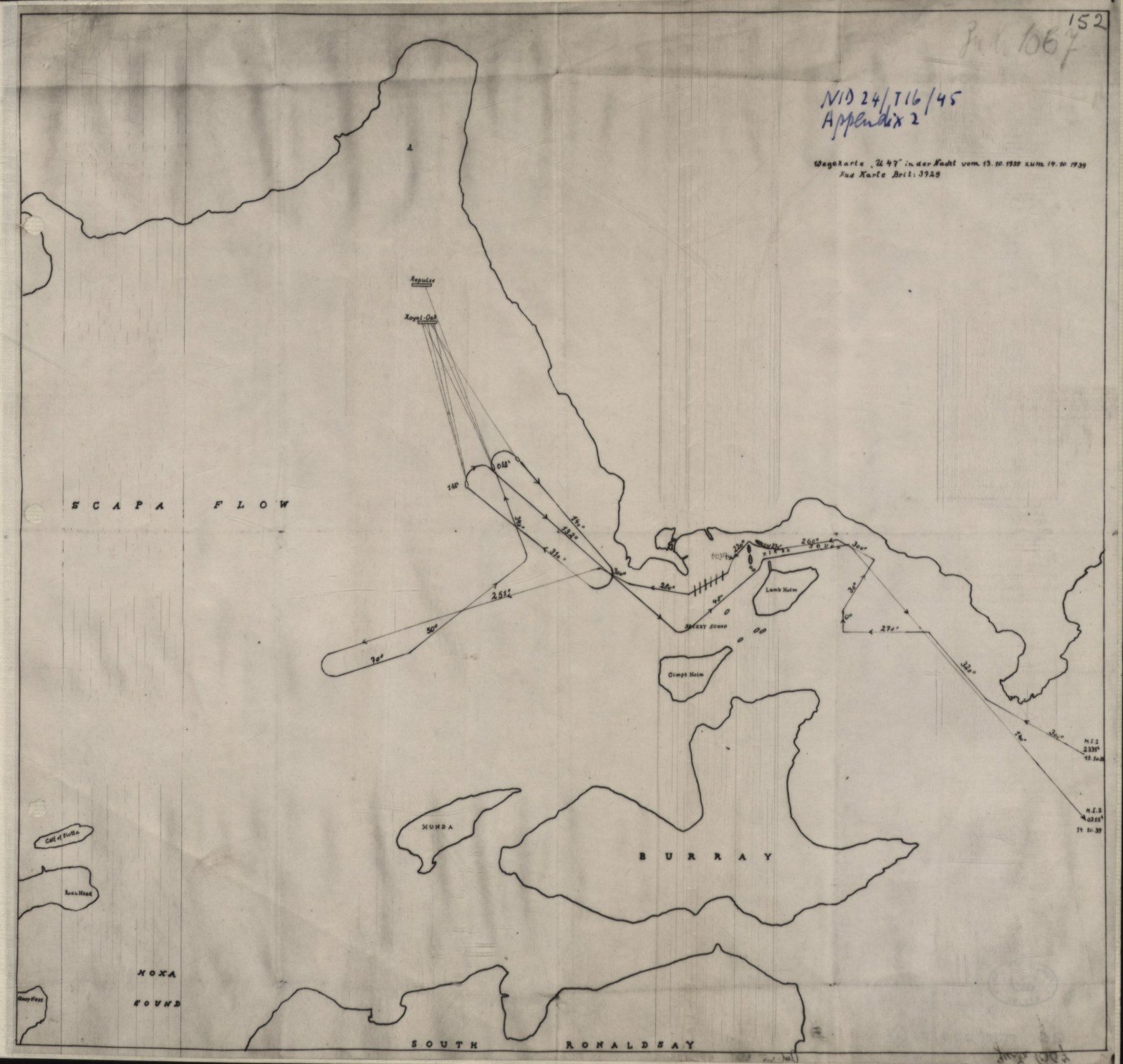

On Friday 13 October, the German submarine U-47 was on the east side of the Orkney Islands. The Captain, Günter Prien, had placed the submarine on the seabed where it lay waiting all day. It was not until 19:15 that the submarine broke the surface and slowly began its journey westward towards the target of mission Sonderunternehmen P – Scapa Flow.

The Northern Lights danced in the sky as the u-boat continued its journey towards Rose Ness on the east side of Mainland. Everything went according to plan until just after 23:00 when they spotted a merchant ship. It was crucial to the mission that they weren’t discovered, so Prien ordered the submarine to dive. They tried to keep an eye on the ship through the periscope but were then unable to locate the mysterious ship, despite a clear night sky with Northern Lights. They remained submerged for about 20 minutes before breaking the surface again and continued in surface position in a north-westerly direction towards Holm Sound. They passed a partially submerged blockship. They now thought they were approaching Kirk Sound and Prien turned the boat 270 degrees. Obersteurman Wilhelm Spahr, who oversaw the navigation, realised that they were not on the right course and that they were actually in Skerry Sound. U-47 turned starboard and headed for Kirk Sound. They moved slowly along the east side of Lamb Holm before heading west and into Kirk Sound, the route they had chosen in order to reach Scapa Flow. They switched from noisy diesel engines to electric propulsion so that they could avoid detection as they passed the village of St. Mary’s, still sailing in surface position. They had probably not expected that there was a dance event in the drill hall in St. Mary’s. There were many soldiers and Wrens stationed in the area, so buses had been set up from Kirkwall to transport the young people to the party in St. Mary’s.

U-47 had just manoeuvred past a blockship when they were suddenly illuminated by the headlights of a vehicle on shore. The lightbeam moved away from the submarine as the vehicle turned and disappeared. They remained undetected.

Forty-five minutes after passing the blockships in Kirk Sound they were inside Scapa Flow.

The Kriegsmarine’s tactic of luring ships out of Scapa Flow to expose them to attack by the Luftwaffe, meant that Prien had only a few ships in Scapa Flow as possible targets this particular night. It would appear that this operation was not coordinated with Prien´s plans. Photographs taken by German reconnaissance aircraft only days earlier had shown Prien a way into Scapa Flow and his British targets. The overflights had also raised the alarm, and even more ships were sent out to sea.

U-47 first sailed towards Lyness but found no ships in the area and met no resistance, then turned north where HMS Royal Oak, HMS Pegasus and possibly HMS Iron Duke were discovered. There were 51 ships in Scapa Flow in total, 18 of which could be described as battleships.

At 00:55 they spotted a large shadow which they assumed was a ship. The submarine was gliding slowly through the water. Now they believed that the shadow was two large warships in the northeast corner of the base, one partially hidden by the other. They believed the southernmost of these two ships to be a Royal Sovereign class warship. The other they could not identify. Most likely the northernmost of these two ships was the older seaplane carrier HMS Pegasus which was anchored about 1,550 meters from the southern ship they saw. The Royal Sovereign class ship was HMS Royal Oak.

At 00:58 on Saturday 14 October all four torpedo tubes were armed with G7e(TII) torpedoes – and ready to fire. This was an electric motor torpedo that could glide silently through the water and had almost no visible trace of air bubbles that could warn ships that they were under attack. However, the TII was unreliable and with unpredictable performance.

The distance to the target was estimated at 3,000 meters, and the depth was set at 7,5 meters. The torpedo in tube IV failed to launch and remained in the torpedo tube, two went towards HMS Royal Oak and one went towards the northern ship. At 01:04 an explosion was heard on the starboard side of HMS Royal Oak. The torpedo hit far down on the bow and did little damage to the ship but caused a spray of water up the side and onto the foredeck of the ship. None of the other torpedoes exploded. The muffled sound of the explosion and the spray of water created more confusion than panic onboard HMS Royal Oak. It was speculated that it could have been a bomb dropped from an aircraft, whether the spray of water had been caused by an anchor chain or whether it could have been an explosion in a paint room in the forecastle. In any case, the situation was not considered serious enough to man the anti-aircraft gun.

At 01:13, U-47 fired three more torpedoes at HMS Royal Oak. Three minutes later, the first torpedo hit the starboard side just before the front gun turret. A huge explosion shook the ship and just seconds later, the other two torpedoes hit the HMS Royal Oak further aft. The explosions were so violent that the ship began to list alarmingly, and the lights went out. The weather had been fine, so all the ship’s hatches were open. As the list increased, the gun barrels turned and contributed further to the list. Water poured in through the open hatches and men sleeping in their berths were unable to get out in time. It was only minutes before the battleship was sinking. Hundreds were fighting for their lives in the water, trying to swim to shore through thick oil and in freezing temperatures.

The Royal Oak would undoubtedly have stayed afloat longer, and more lives would have been saved if the hatches had been closed; however it is not standard procedure to have all the hatches closed when in a supposedly safe harbour.

At 01:33 – 17 minutes after the first torpedo hit – HMS Royal Oak sank to the depths of her final resting place at the bottom of Scapa Flow. She took with her 835 of her crew, many of them only boys.

Soon Wanja’s fate was also sealed.

Illustration: Route taken by U-47 in and out of Scapa Flow. National Archives MFQ 1/895/1